Regime estimation

In this section, we describe methods for estimating the vibrational regime of a bowed string given the different time series a model can provide, which we call probes, during a simulation with some bowing parameters.

In all techniques, the algorithm is applied to a part of the signal which is assumed to vibrate under the same regime. It is then possible to apply it to different parts of the signal to see how the regime evolves over time, or to apply it to different signals produced under different bowing or model conditions and see how the regime changes depending on them.

The methods will change depending mostly on which data or probes the model provides and which regimes have to be discerned. The available probes depend largely on the model being used, and there is not much we can do about it. However, the set of regimes to discern are something decided post-hoc and that we will choose depending on the application - although detecting some extreme regimes will necessarily mean bowing the instrument with certain parameters that we should know beforehand.

Regime sets

There are two large groups of regime sets that we can use: discrete or symbolic, where the regime takes a finite number of values that represent distinct categories (e.g. proper Helmholtz vibration or otherwise), and continuous or descriptive, where the regime is a number or vector that describes the vibration in a generic way (e.g. the mean harmonic-to-noise ratio, or the mean pitch). Sometimes it is possible to relate two regime sets; for instance, we may estimate the regime within a symbolic set given a regime descriptor and some thresholds.

In this project, we will be dealing mainly with two symbolic regime sets: one that tells us whether the current regime is the one described by Helmholtz or not, and another that uses a classification similar to the one in (Raman, 1918): Anomalous Low-Frequency oscillations (ALF), Multiple Stick-Slip cycles (MSS), Aperiodic motion, Helmholtz motion, and continuous slipping (or sticking). For this latter case, we have devised a color palette that we use consistently in plots on our works.

The color palette used when representing our regime set

The color palette used when representing our regime set

Regime detectors found in the literature

There are different methods mentioned in the literature for computing the regime of a simulated bowed string. The first article that mentions the numerical estimation of vibrational regimes in simulated bowed strings is (Woodhouse, 1993), in which the author suggests driving a nonlinear model with a variety of inputs that sweep a space in order to get a map, a la Mandelbrot. He suggests simulating a note with a duration of 100 expected period lengths. Then, the string velocity corresponding to the last five periods is used for good tone estimation. He computes the correlation between what are expected consecutive periods and, therefore, a high value will indicate that there is indeed periodic motion. This oscillation will have a rate either equal to the expected or to one of its multiples. If that is the case, the number of slipping regions within each period is estimated (a slipping region corresponds to a negative velocity, opposed to the bow movement), and if it is greater than one the segment is discarded, attributing to a higher regime of multiple stick-slips. The author already acknowledges that there are difficulties when partial multiple slips appear, and that this algorithm is very rough and calls for future revision. Nevertheless, the authors of (Serafin, 1999) used the very same method when comparing different formulations of the model and different trade-offs.

Regime detectors for our extended regime set

In (Llimona, 2015) we estimated the regime by applying the YIN pitch detection algorithm on the transversal velocity of the string (horizontal polarization) under the bow. This gave us two time series, one for the pitch and the other for the aperiodicity of the signal. These new signals had been computed using a sliding window. From there, we checked some statistics (mean pitch and aperiodicity) against manually tuned thresholds for determining the regime.

The strongest point of this technique is that, although not as accurately, it would still work using probes that most models (even real recordings) could provide, such as the force at the bridge (which is just a displaced and filtered by the driving point admittance version of what we were using) or even the radiated audio itself, if there is no reverberation and changes are smooth enough to not interfere with the long decay of modal vibrations in the body.

It has a major flaw though, which is that the pitch detector tends to make octave errors - which have a direct impact on the regime being accurately detected. This is especially relevant in edge cases where, for instance, the string vibrates mostly at twice its expected frequency (MSS), but every two cycles there is a much larger oscillation, which would correspond to regular Helmholtz motion.

Our custom regime detector

In this project, we designed a new detector that relies on whether the string is actually slipping or sticking at each time step. In the model we are using, detailed in (Maestre, 2014), this state appears explicitly in the equations, and is therefore easy to obtain programatically. In fact, since the model has a finite bow width, we have access to the sticking state of each of the equivalent bow hairs. In this algorithm, we chose to construct a binary variable that tells us whether at least one of the equivalent bow hairs is in a stick state.

Since there could be some noise in the signal, especially in nearly-aperiodic regimes, we found that it benefits from a light smoothing filter based on hysteresis: all samples that leave the stick state which have not been sticking for more than a predefined amount of time are set back to slipping.

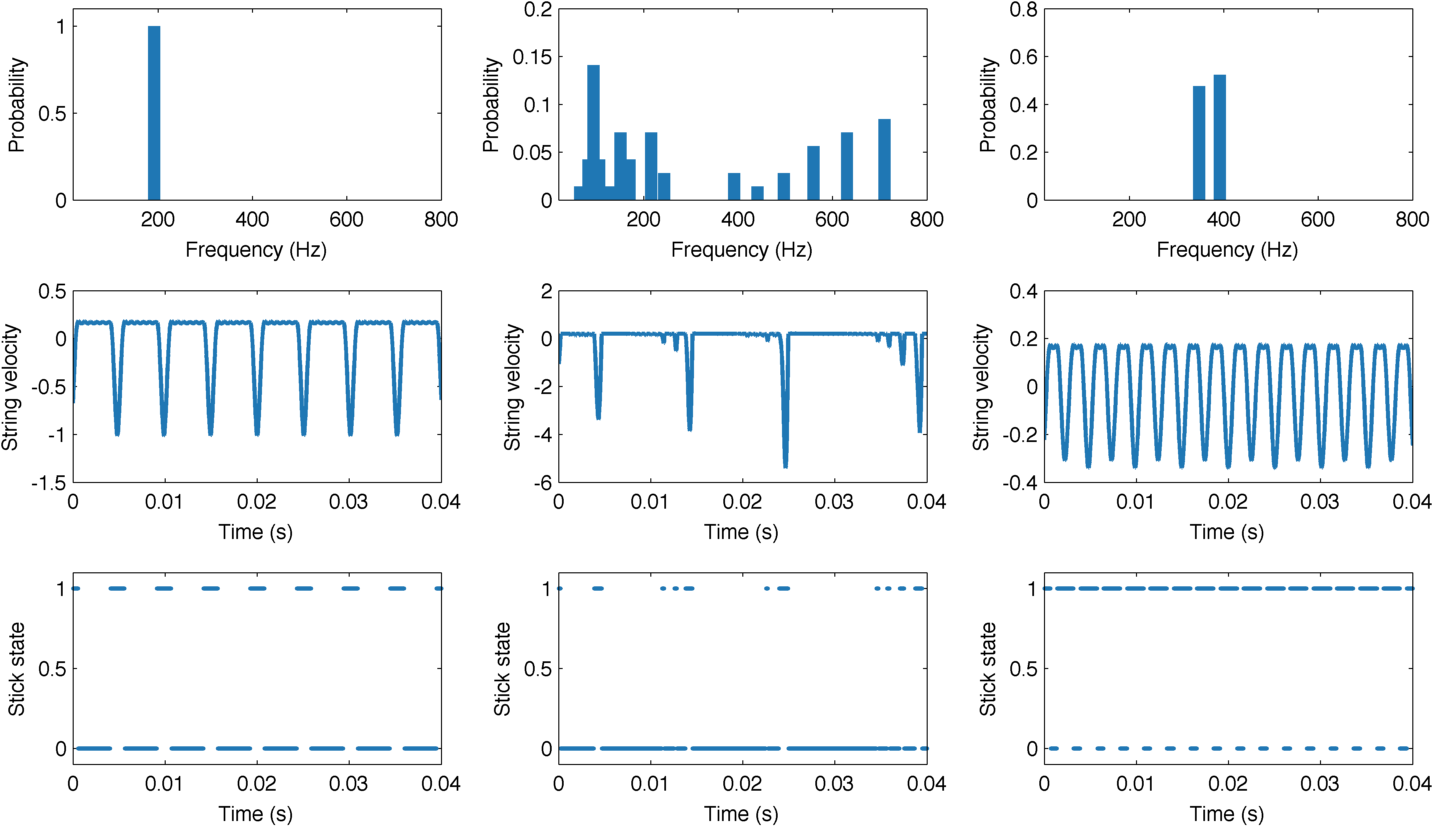

Once we know if there are hairs in a stick state, we compute the time interval between consecutive transitions from slip to stick. When the motion is periodic, this interval will be constant across different transitions along the note. We are interested in the inverse of this interval, which is the frequency at which the string would oscillate if the motion was indeed periodic. The regime detection will be based on statistics over this list of estimated vibration frequencies.

After some exploration, we found that this signal is very clean in the steady state. By computing its histogram, a naive algorithm can easily determine if the signal is aperiodic (the histogram is very flat), in a MSS regime (the histogram shows a big peak at a significantly higher frequency than the pitch we told the synthesizer to play), in an ALF regime (the opposite), or Helmholtz (the peak is where we expected it to be).

We also designed another regime descriptor based on this list of expected frequencies, called helmholtzness, which looks at the percentage of periods that are close enough to the frequency that we were expecting, where “close enough” leaves enough room to account for effects such as flattening but it is narrow enough to avoid capturing aperiodic regimes as periodic. This is helpful in high-level analyses where we only want to know whether the string is vibrating in the ideal (Helmholtz) regime or not, as easily found by thresholding the descriptor.

String velocity under the bridge, stick/slip indicator, and the detailed histogram of inter-slip intervals

String velocity under the bridge, stick/slip indicator, and the detailed histogram of inter-slip intervals